Contribute to the next edition of Groundwork USA’s environmental justice literacy curriculum! If you are interested in being part of further testing Learners to Leaders, please fill out this form or contact maria@groundworkusa.org.

How do you define “environmental justice”?

- “… when both sides of an economic and environmental problem receive equal benefits and burdens.”

- “… the opportunity for all communities to have a healthy living and environment without discrimination.”

- “… fighting for the environment together as people — not just ‘nature’ but the world.”

- “… when you treat everyone and everything with respect.”

These are some of the definitions of environmental justice offered by Groundwork Green Team youth from across our network who’ve been testing Learners to Leaders, Groundwork USA’s new environmental justice literacy curriculum. The curriculum aims to teach youth (and adults) about the history of environmental justice, how to organize in their own communities, and how to research and find information about environmental issues that are affecting their homes and neighborhoods.

Loosely speaking, “environmental justice” describes a movement at the intersection of the American civil rights and environmental movements that became enshrined in federal law in 1994 when President Clinton issued Executive Order 12898, directing federal agencies “to identify and address the disproportionately high and adverse human health or environmental effects of their actions on minority and low-income populations…” This action led to the founding of the EPA’s Office of Environmental Justice. But the origins of the movement, and the work to achieve environmental justice, are “rooted in the power and mobilization of people on the ground,” in the words of one of the movement’s respected leaders and scholars, Vernice Miller Travis. Today, it is still communities working and organizing on the ground that carry the banner of environmental justice.

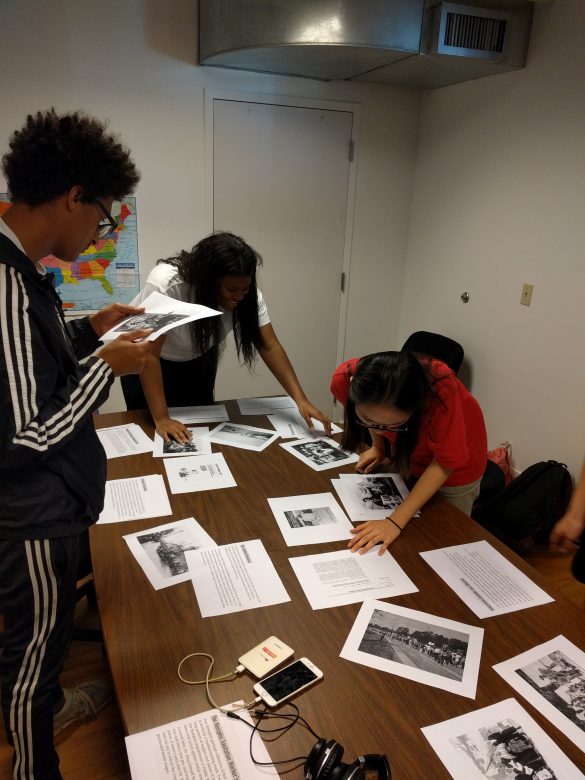

Groundwork New Orleans Green Team youth build an Environmental Justice Timeline, learning about signature environmental justice moments throughout history. Photo: Rebecca Berry

Learners to Leaders EJ Literacy Curriculum — Rooted in the Community

Like the EJ movement itself, the curriculum was invented by youth and community leaders who do the work of environmental justice work. The idea for the curriculum emerged when Groundwork Richmond (CA) program staff and Green Team youth identified a need for greater EJ literacy in Groundwork youth programs. Groundwork Richmond Deputy Director Matt Holmes drafted the curriculum, then brought it to Groundwork USA staff, who further refined it. Groundwork USA has since been testing Learners to Leaders with Groundwork Trusts throughout the country, incorporating feedback from Green Team youth and youth leaders to make it into a more robust, well-rounded program.

Innovative and Adaptable Learning and Teaching

The curriculum utilizes best practices in learning theory — addressing multiple learning styles by incorporating a variety of visual media, interactive and physical activities, readings, and auditory information. The lessons are ideal for after-school, job training, and workplace training programs because they get people up and moving. The curriculum also aims to make history fun by connecting the past with current events, as well as local issues youth experience on a daily basis.

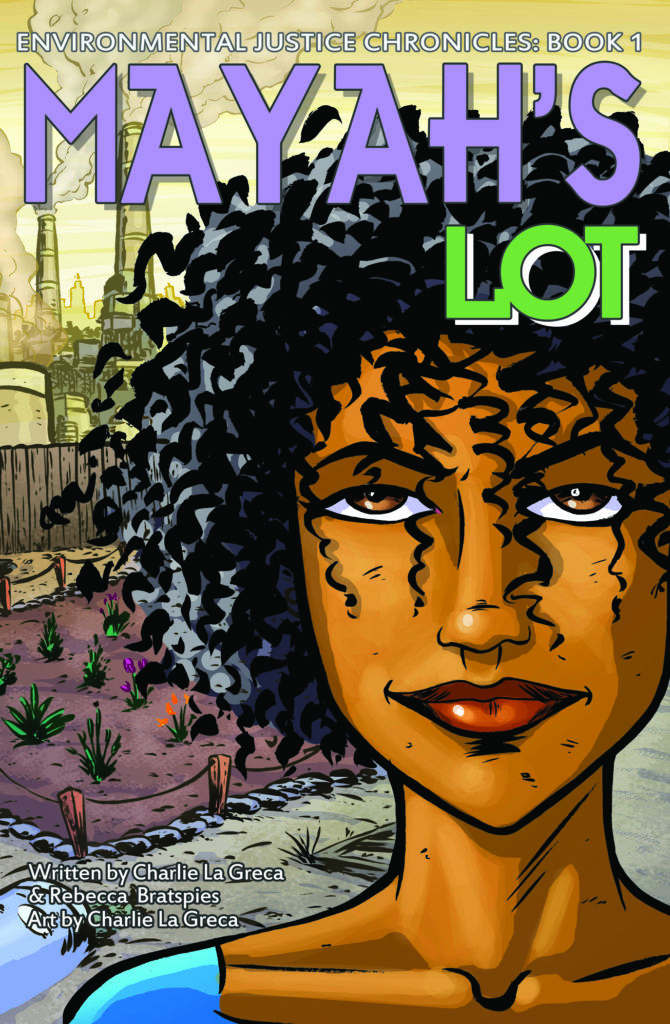

The curriculum begins with reading and/or viewing Mayah’s Lot, an EJ-themed graphic novel and video developed at the Center for Environmental Reform, City University of New York School of Law.

Learners to Leaders stimulates critical thinking skills and can fulfill national education standards in literacy and science. Students learn about information sources, research methods, and problem solving through data gathering and planning.

We’ve made it adaptable to learners of all ages, from middle or high school students to adults. And it can be completed in three days, or extended, through optional materials and activities, into many different kinds of long-term projects. It’s also ideal for small and low-capacity organizations that may not have a lot of time for training. While instructors should have a basic understanding of environmental justice, our hope is that they can learn collaboratively with students, growing into the subject and as they explore the materials in depth and organize around critical environmental issues in the communities where they live and work.

Workshopping the Work

Groundwork USA is currently in the process of getting the word out about our environmental justice curriculum while also soliciting feedback in order to continuously improve it. This past spring, Matt Holmes and I had the opportunity to present workshops on Groundwork USA’s environmental justice curriculum at the 2018 National Environmental Justice Conference and River Rally 2018. We were struck by the level of energy and excitement with which the curriculum was received by audiences of academics, researchers, NGOs, and public officials from around the country, and the feedback we gained from these workshops has been incorporated into the latest version of the curriculum.

Why Environmental Justice?

Historically, the mainstream American environmental movement has treated “the environment” as a physical space to be conserved, largely ignoring the ways in which human communities interact with and depend upon their natural and built environments. As a result, the rights and needs of whole populations have been ignored. Environmental policy, largely driven by recreational interests, has often excluded indigenous peoples and treated indigenous rights as a separate issue. Cities, too, were often excluded from environmental considerations, even though urban residents experience environmental issues like industrial pollution and lack of access to natural areas. These populations are often the first to be affected by environmental hazards and disasters and have the hardest time recovering, due to socioeconomic factors and historical lack of representation.

EJ Literacy Curriculum workshop participants learn about systemic inequality through a fun role-playing game, in which groups compete to complete a project – but the groups are given different materials to work with. Photo: Maria Brodine

At the same time, there has been a prevailing myth that underserved communities don’t care about the environment. In reality, data on the subject are largely shaped by biased research and surveying — again due to the fact that environmental issues are often approached through the narrow lens of recreation and conservation of “wild” spaces. In reality, the history of civil rights and indigenous movements—domestic and international—is full of people organizing to campaign for better access, better representation, better and healthier spaces to live, work, and play. These movements form the foundation of the environmental justice movement we know today. Learners to Leaders Environmental Justice Literacy Curriculum workshop participants learn about systemic inequality through a fun roleplaying game, in which groups compete to complete a project — but the groups are given different materials to work with.

As a network of grassroots organizations, Groundwork USA is deeply involved in environmental justice, both at the community and national levels. As an environmental organization that centers people and the places where they live, work, and play, we are continuing to develop educational tools and resources to aid other organizations in advancing their environmental justice work.

This article is cross-posted from the Groundwork USA Network Blog.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks