How the Federal Government Got There

The early days of the urban environmental movement mostly excluded people of color and low-income residents who were actually exposed the most to pollution. Movements, like the Memphis Sanitation Strike of 1968, drew national attention and raised the issues of not only civil injustice but also environmental injustice. Public health remained a concern for communities fighting for civil rights, who knew that they were at risk from their surrounding environment.

“Whether by conscious design or institutional neglect, communities of color in urban ghettos, in rural ‘poverty pockets’, or on economically impoverished Native-American reservations face some of the worst environmental devastation in the nation.” Professor Robert Bullard, Confronting Environmental Racism: Voices from the Grassroots, 1993

In 1987, the United Church of Christ Commission on Racial Justice’s landmark paper—Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States—finally unequivocally identified race as the most significant indicator for the location of hazardous waste facilities. Environmental justice then made its way to the federal government in 1992 when the EPA created the Office of Environmental Equity which became the Office of Environmental Justice in 1994 after President Clinton released Executive Order 12898 – Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations. Today, the Office of Environmental Justice, among other initiatives, provides grants to communities and has created the EJ Screen tool to map community vulnerability. [See more details about the Environmental Justice Movement with EPA’s Environmental Justice Timeline.]

More recently, Senator Bernie Sanders and Representative Bennie Thompson requested in 2019 that the Government Accountability Office (GAO) provide an assessment of the government’s performance on initiatives laid out in the 1994 executive order. What followed was the report Environmental Justice: Federal Efforts Need Better Planning, Coordination, and Methods to Assess Progress. The GAO recommended that agencies update environmental justice strategic plans and report annual progress. In all, there were 24 specific recommendations that can be found here.

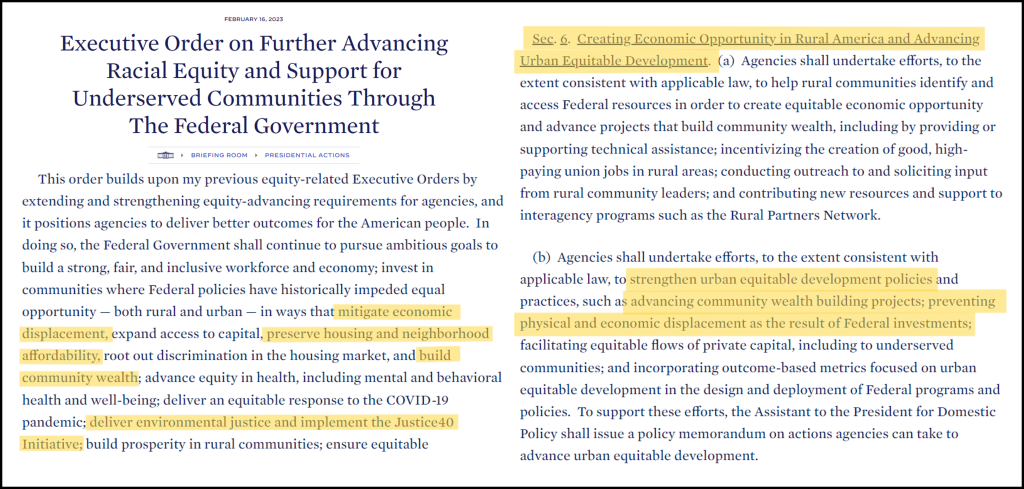

Environmental justice and racial equity work continue to evolve at the federal level. On January 20, 2021, the Biden administration issued an Executive Order on Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government that includes equity in policy making, investments in infrastructure, and community reconnections. Still, barriers exist in historically divested communities. So, building on the progress from the original order, the White House released the Executive Order on Further Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government on February 16, 2023.

How UWLN has been Engaged in this Work

The Urban Waters Learning Network (UWLN) and its members are happy to see this work continue.

“It’s wonderful to have the recognition of what the country should be doing.” – Gloria McNair, Groundwork Jacksonville

We see that the executive orders relate to the work that the UWLN has been doing for years, particularly with the UWLN Equitable Development and Anti-Displacement Collaborative. The highlighted sections from the February Executive Order—mitigating displacement, preserving affordable housing, building community wealth, implementing environmental justice and Justice 40—are places in which our work intersects with the directives.

While the order directly impacts federal investments, racial equity and anti-displacement are concepts that anyone can use. If you’re wondering how to apply these concepts into your environmental work, we have many resources from our collaborative and other network members.

Mitigating Displacement

- Webinar: Understanding Gentrification and Displacement: The Path to Equitable Development

- 11th Street Bridge Park – Equitable Development Plan by the 11th Street Bridge Park Equitable Development Task Force

- Not in Cully: Anti-Displacement Strategies for the Cully Neighborhood by Portland State University

Affordable Housing

- Webinar: Anti-Displacement Strategies… Environmental Restoration Meet Affordable Housing

- Toolkit: What About Housing: A Policy Toolkit for Inclusive Growth by Grounded Solutions Network

- Report/Guide: Pathway to Parks & Affordable Housing Joint Development by LA THRIVES and Los Angeles Regional Open Space and Affordable Housing Coalition

Community Wealth Building

Environmental Justice and Justice 40

- Webinar: Exploring the Intersections between Environmental Justice and Equitable Development in Infrastructure Investments

- Blog: Q&A from Peer Learning Session: Environmental Justice and Equitable Development

Other ways that our work intersects with the Feb, 2023 EO

- Webinar: Building Community Leadership as an Anti-Displacement Strategy

- Video Series: Addressing Racial Equity

- Blog: Urban Waters Impacts on Racial Equity, Environmental Justice, and Equitable Development

- Recorded Learning Session: Leading with Equity for Flooding Resilience and Investments in Water Infrastructure